David G Taylor explores how British art is laid bare this spring.

It’s that time of year in London when daytime lingers a little longer, and across the capital’s many wild green spaces, native flowers such as primroses and wild daffodils begin to bloom. As Mother Nature reaches for the sun, it seems fitting that British landscape painting and its creators, in a sense, are also coming to light.

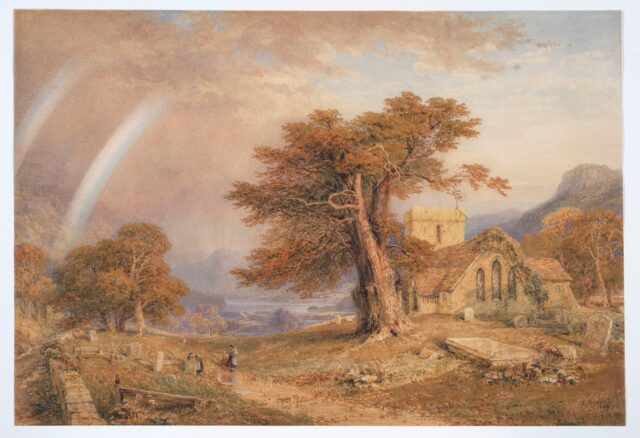

The Courtauld Gallery’s first exhibition of 2026 is determined to rescue 10 names from the shadowy fringes of art history. Creating in an era heralded as the ‘Golden Age of British Landscape Painting’, these artists have been left in the darkness of obscurity due only to gender bias. A new show, A View of One’s Own: Landscapes by British Women Artists, 1760-1860 (to 20 May), seeks to right this injustice by turning a spotlight on some startling female talents, often overlooked, largely unknown and mostly unpublished.

Reclaiming The Landscape

Elizabeth Frances Batty, later Martineau (1791-1875) is one of the artists being reappraised. Only recently rediscovered, she was the daughter of a physician who was an amateur artist himself. It was to him that she dedicated her only known published work – a book of 62 extemporary original engravings. Titled Italian Scenery. From Drawings Made in 1817, her book has languished forgotten and, despite her exceptional artistry, other works by Batty have yet to be identified.

A pupil of the prolific English painter Peter De Wint, Fanny (Frances) Blake (1804-1879) was an amateur artist working in watercolour and graphite whose compositions included spectacular views of England’s Lake District. Little is known of her outside an 1851 exhibition review in The Gentleman’s Magazine, describing her as an ‘accomplished artist, admirable for truth, completeness and delicacy’.

Artist Amelia Long (Lady Farnborough, née Hume) is one of the exhibition’s more familiar names due to her exceptional creativity and impeccable connections. In 1819, her friend and poet William Wordsworth dedicated a poetry anthology to her, and in the 1870s her portrait was famously painted by Joshua Reynolds. Alongside her brilliant studies of botanical specimens and the beautiful landscapes of Kent, she was also one of the first intrepid artists to travel to France following the Napoleonic Wars, documenting the post-war landscapes of 1815-17 and the conspicuous presence of British troops still stationed there.

It’s ironic that, beyond their connections to notable men of the day, there is little information to be found about the lives or artworks of many of these previously unsung artists, which rather highlights the great need for exhibitions of this sort. However, this isn’t the only exhibition of the season to spotlight art’s greatest Britons.

A Life Laid Bare

By contrast, contemporary artist Tracey Emin is a female British artist who has achieved recognition in her lifetime. Yet this wasn’t always so. In the 1990s, Emin shocked many with her confessional work and sheer audacity. The tent she appliquéd with the names of everyone she’d slept with up to then caused a scandal, and then there was her ready-made sculpture, My Bed, from 1998.

With its stained and dishevelled sheets and surroundings strewn with rubbish, it recreated the setting of an alcohol-fuelled breakdown she’d had. Yet, it was a far cry from the aesthetically pleasing pictures that the gallery-going masses expected from artists, and I’d argue that Emin received a harsher press than her male contemporaries Damien Hirst and Gavin Turk.

Now a bona fide dame and national treasure, it’s easy to forget Dame Emin’s initial struggle to be taken seriously. However, a new retrospective exhibition at Tate Modern offers an opportunity to reappraise her entire 40-year career with fresh eyes.

Billed as the ‘largest ever survey’ of Emin’s work, Tracey Emin: A Second Life (27 Feb-31 Aug) features more than 90 artworks, including paintings, videos, textiles, neons, sculptures and installations. Visitors get a rare chance to see photographs of Emin’s 1980s art-school paintings which she later destroyed alongside the bed that stoked so much controversy on its Turner Prize nomination. Emin’s infamous tent was accidentally destroyed in a warehouse fire, but there are other pivotal textile works on show, such as the 1997 appliquéd blanket, Mad Tracey from Margate. Everybody’s Been There.

Emin’s autobiographical art is often poetic and sometimes confronting. She doesn’t shy away from expletives, uncomfortable revelations or graphic imagery and the works on show often explore her personal traumas. None more moving, perhaps, than the 1995 video, Why I Never Became a Dancer, in which she recounts her turbulent adolescence in the rundown English seaside town of Margate, Kent, including sexual abuse. Margate is where Emin is once again based, making a significant contribution to the town’s upturned fortunes.

Emin’s life and death battle with bladder cancer in 2020 and the stoma she lives with are also explored in her work. In fact, the show’s title, A Second Life, refers to her post-op era and works such as her 2024 bronze sculpture Ascension exploring suffering, catharsis and rebirth.

However, an earlier piece, The Last of the Gold from 2002, must be one of the exhibition’s biggest highlights. A quilt embroidered with Emin’s ‘A to Z’ of advice to women about the realities of having an abortion, it has never been exhibited before. Emin describes the exhibition as ‘a true celebration of living’, commenting: ‘I feel this show… will be a benchmark for me… a moment in my life when I look back and go forward.’

Britain, Now

Across the city, at the Mall Galleries, is an opportunity to discover a wide range of British contemporary artists working in many mediums, as the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA) stages its Annual Exhibition (26 Feb-7 Mar). This group show not only features work by the society’s members but also a selection of non-members handpicked from submissions. Among this year’s most notable exhibitors is Ken Nwadiogbu, the most recent recipient of the RBA Rome Scholarship. Nigerian-born and based in London, he’s best known for creating incredibly detailed, hyper-realistic images in charcoal, pencil and acrylic, including lifelike portraits of people peering through ripped paper. A series of special events will accompany the exhibition, including the RBA Annual Lecture featuring a Q&A session with Nwadiogbu (28 Feb).

Seasons of change

One the originators of the Pop Art movement in the 1960s, and still going strong in his late eighties, Yorkshire artist David Hockney’s most recent work is showcased in London’s Serpentine North Gallery this year.

The exhibition, simply titled David Hockney (12 Mar-23 Aug) centres around his imposing 90-metre-long landscape, A Year in Normandy (2020-21). The frieze was inspired by Normandy’s famous 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry, the medieval textile depicting the conquest of England by the French in 1066. The invasion that changed Britain forever was led by the Duke of Normandy (later crowned King William I aka William the Conqueror). Instead of war, Hockney’s frieze depicts the battling seasons of winter, spring, summer and autumn, as witnessed outside the artist’s former studio in Normandy.

It’s the first time A Year in Normandy has been exhibited in London, and the exhibition is perfectly timed ahead of the highly anticipated return of the Bayeux Tapestry to England after more than 900 years. On loan to The British Museum, it will be on show from September 2026 to June 2027 – an historic moment.

Besides Hockney’s frieze, the Serpentine show is made up of new and recently created artworks not previously exhibited, including some of his Sunrise and Moon Room series. The veteran artist has long been interested in creating experimental art with modern technology, as evidenced with his cubist Polaroid collages in the 1980s, and many of these landscapes were created on an iPad or iPhone. Although he’s always painted outdoor scenes, Hockney has become increasingly known for his landscapes which explore lunar cycles, changing light and the passage of time. This is Hockney’s first exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery, so there are many reasons making this a show not-to-miss.

Drawing the line

Girl in Bed, 1952, Lucian Freud, Oil on canvas © The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2025 | Bridgeman Images. Photo © National Portrait Gallery, London. Lent by a private collection, courtesy of Ordovas, 2014

British realist Lucian Freud (1922-2011) is best known for oil paintings, such as his fleshy nude of fashion icon Leigh Bowery, and Bowery’s friend and biographer Sue Tilley.

Freud became international news in 2008 when one – Benefits Supervisor Sleeping – scored the then highest price ever paid for a painting by a living artist, selling for £17.2 million.

A new National Portrait Gallery exhibition, however, goes beyond the hype for an intimate look at the artist and his pencil studies. Lucian Freud: Drawing into Painting (12 Feb-4 May) is a landmark exhibition exploring Freud’s obsessive drawing practice, his creative process and the dialogue between his sketches and paintings.

It’s an exhibition uncovering reoccurring motifs, the evolution of the artist’s style, through artefacts including 48 sketchbooks, childhood drawings, exploratory studies, unfinished paintings, love letters and other objects offering insight. Among more than 170 drawings, etchings and paintings, notable works include an oil portrait of artist and friend David Hockey, etchings of Freud’s daughter and fashion designer, Bella Freud, and ambitious artworks created in response to historic paintings by John Constable and Jean-Antoine Watteau.

Blazing a trail

Cats, current affairs and celebrities on the red carpet are among the things depicted in the works of Rose Wylie. The multi-award-winning British contemporary artist obsessively paints imagery seared into her memory including personal experience and pop culture. Her mind’s eye is a vast repository of visual references that bleed into her playful paintings in often unexpected combinations of child-like drawings and written text. These include recollections of her World War II-era childhood (Rosemount, 1999), self-portraiture (Bottom Teeth, 2016), her creative process (HAND, Drawing as Central, 2022), and scenes gleaned from English TV and worldwide cinema (Snow White with Duster, 2007).

Recognition came later in life for Wylie, only rising to prominence in her mid-seventies with a 2013 solo show at London’s Serpentine Gallery. Blazing her own trail, her work perhaps didn’t easily fit into movements and trends, but her status cemented internationally when she represented Britain at the Venice Biennale of 2017 in her eighties. Now aged 91, it seems fitting that more than 90 of Wylie’s works are to be exhibited this spring, as the Royal Academy of Arts stages Rose Wylie: The Picture Comes First (28 Feb-19 Apr).

Wylie often works on large-scale unstretched canvases, but visitors will be able to see her paintings and her works on paper. Ranging from famous drawings and paintings to works never exhibited before, this will be the largest survey of the artist’s work ever staged.

As spring unfolds, these exhibitions collectively offer a portrait of British art in the round and invite us to look again at whose stories have been framed and whose are still waiting to be brought into the light.

Curate your own collection

If these exhibitions whet your appetite for art, then spring brings opportunities for pieces to take home.

Held at Somerset House, Collect 26 (26 Feb-1 Mar; invite-only preview 25 Feb) finds more than 40 galleries showing ceramics, furniture, glass, jewellery, metalwork, sculpture, textiles and wearable art by emerging and established artists.

Parallax London (28 Feb-1 Mar), Europe’s largest fair of independent artists and designers, boasts more than 300 exhibitors showing tens of thousands of works amid the grandeur of Chelsea Old Town Hall.

The Affordable Art Fair (4-8 Mar) pops up in south London’s beautiful Battersea Park. Inside, galleries showcase thousands of original contemporary artworks, some priced from as little as £100.